Dernière mise à jour : 14 mai 2019

Détails

Gamme de produits:

Examen d’une technologie de la santé

Numéro de projet :

ES0313-000

Final Biosimilar Summary Dossier Issued:

(Le contexte est en français. La suite du document est en anglais.)

Contexte

La douleur chronique non cancéreuse (définie dans le cadre de ce rapport comme toute condition douloureuse persistante pour au moins trois mois et non associée à une affection maligne9) affecte approximativement 20 % des adultes au Canada1. On estime que les couts directs la douleur chronique non cancéreuse pour le système de santé canadien sont de l’ordre de 6 milliards $ par année, alors que les couts en productivité associés à la perte d’emploi et aux journées de maladie sont estimés à plus de 37 milliards $ par année2.

Au Canada, les services de gestion de la douleur chronique sont actuellement fragmentés entre les systèmes public et privé, le secteur public se concentrant surtout sur les traitements médicamenteux3. En ce moment, dans le secteur public, les opioïdes représentent l’option de choix, malgré leur efficacité à long terme limitée chez certains patients, partiellement en raison de l’apparition d’une tolérance à leur effet analgésique. On est de plus en plus conscients des risques associés aux opioïdes, comme le détournement, la dépendance, les surdoses et l’augmentation des décès5. Selon un rapport publié par l’Institut canadien d’information sur la santé, les empoisonnements par opioïdes au Canada ont été la cause de 16 hospitalisations par jour en moyenne entre 2016 et 20176. De janvier à septembre 2017, on a relevé au moins 2 923 décès apparemment liés aux opioïdes7.

Plusieurs initiatives et guides de pratique ont été mis en œuvre au Canada afin de promouvoir l’usage adéquat des opioïdes. Ces efforts ont connu divers degrés de succès et ont eu des répercussions incertaines sur les résultats importants que sont la prescription de grandes doses d’opioïdes et les hospitalisations dues aux opioïdes9. L’un des enjeux importants réside dans le manque d’options de traitement claires et les obstacles à la mise en œuvre — comme l’accessibilité, l’intégration au traitement et le financement — de programmes offrant des stratégies fondées sur des médicaments non opioïdes ou des stratégies non médicamenteuses.

La crise des opioïdes a mis en lumière le besoin de repérer les stratégies optimales de gestion de la douleur chronique. Les thérapies non médicamenteuses sont considérées comme une composante majeure d’une approche multidisciplinaire qui est de plus en plus mise en avant dans le traitement de la douleur chronique10. Pour les besoins de ce rapport, le « traitement non pharmacologique de la douleur » signifie les interventions qui ne font pas usage de médicaments ni d’aucun principe actif ou d’intervention chirurgicale (à moins qu’elle soit nécessaire pour la procédure ou les dispositifs impliqués dans l’intervention non médicamenteuse) pour traiter ou gérer la douleur10,13. Les procédures chirurgicales ont été exclues afin de se concentrer surtout sur les interventions non médicamenteuses pour la douleur qui ne seraient pas effectuées dans le milieu hospitalier. Des interventions mettent l’accent sur l’altération des facteurs physiques, cognitifs et comportementaux qui peuvent être associés à la condition causant la douleur et obtenir un large éventail d’effets bénéfiques allant du soulagement de la douleur à l’amélioration des compétences d’adaptation du patient13,16. Les thérapies non médicamenteuses pour la douleur peuvent être une alternative à la pharmacothérapie et l’intervention chirurgicale, bien qu’elles soient habituellement considérées comme complémentaires à une approche multidisciplinaire de gestion de la douleur15.

Les traitements non médicamenteux peuvent être administrés par des professionnels de la santé, d’autres prestataires de services de gestion de la douleur et par le patient lui-même. Ils peuvent être administrés dans différents milieux, comme dans des centres de soins de santé et de traitement de la douleur, au domicile du patient ou à distance en utilisant des méthodes assistées par les technologies17. Les interventions non médicamenteuses contre la douleur proviennent d’un éventail de disciplines, approches et techniques; pour les fins de ce rapport, nous les avons divisées en grandes catégories, interventions physiques et interventions psychologiques.

Tableau 1 : Exemples d’options non pharmacologiques aux opioïdes dans la gestion de la douleura

| Non pharmacologique — physiquea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procédures/interventions | Dispositifs médicaux | Thérapies manuelles | Exercice/condition physique | Autres | |

|

Exemples :

|

Exemples :

|

Exemples :

|

Exemples :

|

Exemples :

|

|

| Non pharmacologique — psychologiquea | |||||

| Administré par un professionnel de la santé | Administré par un professionnel, un prestataire ou en autogestion | ||||

|

Exemples :

|

Exemples :

|

||||

a Note : Cette liste n’est pas exhaustive.

b Modalités de traitement physiques nécessitant une intervention chirurgicale. Ces traitements peuvent impliquer l’administration d’agents pharmacologiques, mais, aux fins du présent rapport, sont inclus pour représenter le fait que la procédure est effectuée avec des agents non pharmacologiques.

c Certains aspects de ces modalités de traitement pourraient être considérés comme psychologiques ou physiques. Aux fins du présent rapport et en raison de la structuration de l’enquête, ces interventions figurent dans les sections consacrées aux traitements physiques.

Les centres multidisciplinaires de traitements dont le personnel comprend divers professionnels ayant de l’expertise en gestion de la colère (c.-à-d. médecins, infirmiers et infirmières, physiothérapeutes et professionnels en santé mentale) offrent une grande variété de traitements, comprenant des modalités non pharmacologiques. Cependant, la gestion des listes d’attente dans les centres multidisciplinaires de traitements est un enjeu partout au Canada19.

Le projet canadien STOP-PAIN a été conçu pour documenter le fardeau humain et économique de la douleur chronique chez les personnes sur les listes d’attente des centres multidisciplinaires de traitement de la douleur19,21. Les constatations résultant de cette recherche indiquent que la médiane de temps d’attente pour obtenir un premier rendez-vous dans un centre multidisciplinaire de traitement de la douleur financé par le secteur public est de six mois au Canada19. Par contre, le temps d’attente dans la plupart des centres multidisciplinaires privés de traitement de la douleur est de moins de deux mois. De plus, les gens vivant à l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard, dans les trois territoires et dans la majorité des milieux ruraux de toutes les provinces ont un accès limité à des traitements adéquats de gestion de la douleur19. La recherche montre également que, durant la période d’attente, les patients subissent des répercussions importantes sur leurs activités quotidiennes et leur qualité de vie en raison des difficultés associées à la douleur aigüe, comme la dépression et l’idéation suicidaire20. En outre, le cout mensuel médian des soins pour chaque patient sur une liste d’attente pour des traitements en centre multidisciplinaire est estimé à 1 462 $ pour des services publics ou privés, ces couts incombant en grande partie au patient lui-même et comprennant les couts en perte de temps (incluant le temps d’absence au travail du patient ou des membres de sa famille) et les couts d’assurance privée21.

L’abordabilité des soins de santé est l’un des enjeux importants en gestion de la douleur3. En 2017, un rapport de l’Association canadienne des compagnies d’assurances de personnes estime à 25 millions le nombre de Canadiens et Canadiennes (environ 80 % de la population) qui souscrivent une assurance maladie complémentaire22. Pourtant, plusieurs personnes paient quand même de leur poche pour des services non médicamenteux dans leur communauté, comme la physiothérapie, la chiropraxie, l’ergothérapie et le counseling psychologique alors que ces services ne sont pas remboursés ou que le montant couvert par leur assurance est atteint3. Ceci génère des difficultés d’accès parce que tous les patients ne peuvent se permettre de traitement à long terme, particulièrement les personnes à faible revenu ou qui n’ont pas d’assurance maladie complémentaire. Comprendre les enjeux qui touchent la disponibilité et l’accessibilité des traitements non pharmacologiques pour la douleur au Canada peut appuyer les efforts pour encourager une meilleure intégration de ces thérapies dans les méthodes de traitement. Par conséquent, une analyse de l’environnement — dont une recherche documentaire, une enquête ciblée et des consultations — sur le contexte actuel de traitement non pharmacologiques de la douleur au Canada a été réalisée dans le cadre des grandes initiatives de l’ACMTS à l’appui de la stratégie canadienne visant à résoudre la crise des opioïdes. Cette analyse de l’environnement vise à fournir des informations sur les services offerts, les facteurs ayant une incidence sur l’accès et les pratiques de financement associées aux traitements non médicamenteux de la douleur chronique non cancéreuse au Canada.

Objectives

The key objectives of this Environmental Scan are, as follows:

- to describe the current context (i.e., available public and private services; guidance for use, level of access/use/integration in treatment pathways; types of providers, treatment settings) around the non-pharmacological treatment of chronic non-cancer pain in Canadian jurisdictions

- to describe the Canadian funding practices related to non-pharmacological therapies for chronic non-cancer pain

- to identify the barriers and facilitators to accessing non-pharmacological therapies for chronic non-cancer pain in Canada.

Patient and public perspectives were not captured within this report. In addition, this Environmental Scan does not address or assess the clinical or cost-effectiveness of treatments for non-pharmacological pain. Thus, conclusions or recommendations about treatment effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, or place in therapy are outside of the scope of this report.

Research Questions

The survey and literature review components of this Environmental Scan aimed to address the following research questions:

- What are the Canadian policies, frameworks, guidelines and other guidance documents related to the use of non-pharmacological pain treatment options for chronic non-cancer pain?

- What are the publicly funded non-pharmacological treatment options available for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain in Canada?

- What are the current funding models for non-pharmacological pain treatment options for chronic non-cancer pain in Canada?

- What are the barriers to availability of and access to non-pharmacological pain treatment options for chronic non-cancer pain?

- What are the facilitators of availability of and access to non-pharmacological pain treatment options for chronic non-cancer pain?

What are proposed strategies for increasing the availability of and access to non-pharmacological pain treatment options for chronic non-cancer pain?

Methods

This Environmental Scan, led by CADTH, was scoped in collaboration with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Chronic Pain Network (CPN). The findings of this Environmental Scan are based on targeted consultations and responses to the CADTH Access to and Availability of Non-Pharmacological Treatment of Chronic Non-Cancer Pain in Canada Survey (the English version is presented in Appendix 24), and a limited literature search. A description of the three approaches follows. Table 2 outlines the criteria for information gathering and selection.

Table 2: Components for Information Screening and Inclusion

| Components | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Patients (of any age) with chronic non-cancer pain Subgroups of interest: pediatrics, geriatrics |

Patients with cancer-related pain |

| Intervention | Non-pharmacological therapies for pain (alone or combined with other treatments for pain)a |

|

| Settings |

|

N/A |

| Outcomes |

|

N/A |

aThe availability of and access to complementary and alternative medicine interventions, homeopathic products, and natural health products were not addressed within this report.

b Primary surgical procedures; interventions requiring surgery for administration are included (see Table 1).

Initial Consultations

Early consultations with experts in the field occurred during the scoping phase for this project and through the STOP-PAIN collaborative survey on multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities. Further consultations with STOP-PAIN collaborative experts and other clinical experts were conducted in developing the survey for this Environmental Scan. These early consultations were not used to generate data for this Environmental Scan but rather to inform the information gathering approach.

Survey

The survey was conducted from March 13 to April 9, 2018. The 18 survey questions consisted of a combination of dichotomous (i.e., yes/no), ordinal and nominal scales (e.g., Likert), and open-ended questions. The questions were designed to probe the following main areas:

- the availability of non-pharmacological treatments and related funding practices

- factors related to access, including patient eligibility criteria, and barriers and facilitators to the availability of and access to non-pharmacological treatments

- guidance, strategies, and solutions being considered or implemented to improve the availability of and access to non-pharmacological treatments.

In addition, the survey opened with questions to gather demographic information about the respondent. Questions requesting permission to follow up with the respondent and suggestions of other potential respondents were posed at the end of the survey.

Survey questions were peer-reviewed by several expert stakeholders prior to distribution. The survey was distributed electronically using the Hosted in Canada Surveys platform to key jurisdictional respondents and stakeholders involved in planning, decision-making, management, and service provision related to the non-pharmacological treatment of pain.

The survey targeted the following types of respondents:

- pain organizations

- clinical experts (pain management specialists, other specialists, primary care physicians, and general practitioners)

- other providers of non-pharmacological pain treatment services (e.g., allied health professionals, nurse practitioners, nurses, mental health practitioners)

- professional organizations related to non-pharmacological pain treatment and seeking to include respondents who could represent the following perspectives:

- different geographical settings (e.g., rural, urban, remote)

- different health care settings (e.g., primary/community [non-specialized and specialized] care)

- different health care roles (e.g., decision-maker, health care provider).

Participants were identified through CADTH’s Implementation Support and Liaison Officer and Opioid Working Group networks, and via stakeholder and expert suggestions, as well as through referrals and social media. All respondents gave explicit permission to use the provided information for the purpose of this report. Information regarding the jurisdictions and organizations represented by survey respondents is presented in Appendix 1.

Literature Search

The literature search was performed by an information specialist using a peer-reviewed search strategy. Published literature was identified by searching the following bibliographic databases: MEDLINE with In-Process records and daily updates via Ovid, the Cochrane Library via Wiley, and PubMed. The search strategy consisted of both controlled vocabulary, such as the National Library of Medicine’s MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), and keywords. The main search concepts were chronic pain AND Canada. No methodological filters were applied. Where possible, retrieval was limited to the human population. The search was also limited to documents published between January 01, 2013 and January 11, 2018. Regular alerts were established to update the search until June 2018. Conference abstracts were excluded from the search results. Grey literature (literature that is not commercially published) was identified by searching relevant sections of the Grey Matters checklist (https://www.cadth.ca/grey-matters). Google and other Internet search engines were used to search for additional Web-based materials. These searches were supplemented by reviewing the bibliographies of key papers and through contacts with appropriate experts and industry.

Post-Survey Consultations

Following stakeholder review of the draft report, the team conducted further consultations to address knowledge gaps. Individuals identified through the stakeholder feedback process and who self-identified via the survey questionnaire as willing to participate in further consultations were engaged. An initial group consultation was held to determine the scope of information gathering required. Subsequently, eight key stakeholders from multiple jurisdictions participated in semi-structured interviews addressing the general themes of the Environmental Scan. These interviews included preplanned questions and the opportunity for open feedback and discussion. The sessions were facilitated by two members of the project team. The stakeholders included two nurse practitioners, one academic researcher, two physicians involved in the management of pain, one physiotherapist, one chiropractor, and one policy specialist. These individuals were involved in the direct management of patients with chronic pain, in program development, or research related to the non-pharmacological treatment of pain. The consultations took place during July and August of 2018.

Synthesis Approach

Only feedback from respondents who gave consent to use their survey information was included in the report. Feedback was excluded when information on a respondents’ occupation was absent or when greater than 75% of the survey was incomplete. Disaggregated jurisdictional data were used to identify any notable similarities or differences existing between jurisdictions regarding availability, access, and funding models for non-pharmacological pain treatments. Rather than analyzing jurisdictional-specific data, responses were pooled and a pan-Canadian approach was used to report on factors (barriers and facilitators) affecting the availability of and access to non-pharmacological treatments across jurisdictions. General trends in the data were described using a narrative approach, with no set thresholds used to define trends. Feedback from open-ended questions was also incorporated into the text. Because of the limited data that was received from Nova Scotia (one respondent), feedback from this province was only included in the pan-Canadian analysis of barriers and facilitators. Articles identified from the literature search and subsequent alerts were screened for selection, and those that met the inclusion criteria (Table 2) were summarized within relevant sections of the report. Feedback was solicited on an earlier draft of the report through an open call to the public, survey respondents, and key stakeholders. This opportunity was promoted through direct invitations, electronic notices, and social media. Feedback received informed the revision of the draft report. Subsequently, information obtained during the post-survey consultations was incorporated. Notes and recordings from the sessions were reviewed by a member of the research team and grouped thematically according to relevant sections of the report. Permission to cite statements as personal communications was requested for new information that could not be cited.

Findings

The findings presented are based on targeted consultations with key stakeholders received by August 28th, 2018, survey results from key respondents received by April 9, 2018), and a limited literature search. Because of the reliance of respondent identification and recruitment on referrals and secondary distribution, it was not possible to quantify the number of individuals who were invited to complete the survey. Upon closure of the survey, 258 responses were received. Of these, 111 responses were excluded for lacking demographic information or for being more than 75% incomplete, and 147 responses were included in the analysis.

Survey questionnaire respondents represented the following provinces: Alberta (15 respondents), British Columbia (36 respondents), Manitoba (eight respondents), New Brunswick (24 respondents), Nova Scotia (one respondent), Ontario (47 respondents), Quebec (12 respondents), and Saskatchewan (four respondents). Because of the lack of responses, perspectives from other provinces (Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island) and the three territories are not represented in this Environmental Scan.

Providers and Treatment Settings Involved in the Non-Pharmacological Treatment of Pain

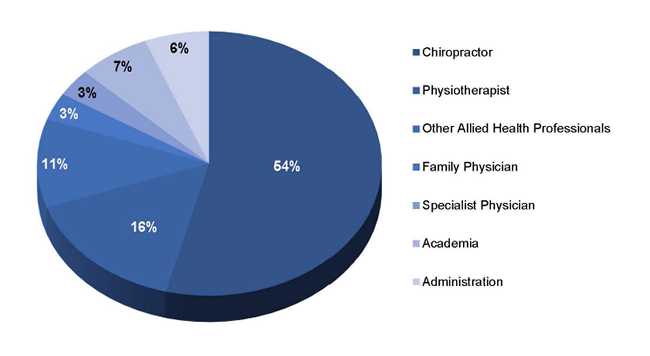

Characteristics of the survey respondents and the organizations represented are presented in Appendix 1. Across the provinces, the majority of responses were received from chiropractors (Figure 1). Responses were also received from other allied health care professionals (including physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurse practitioners, psychologists, and pharmacists), physicians (including family physicians and those specializing in neurology, emergency medicine, anesthesia, and palliative care), those working in academia, and those working in health administration to oversee staff or develop policies for the management of chronic pain.

Figure 1: Respondent Distribution by Occupation

Most survey respondents worked in urban primary care settings, at stand-alone private facilities, or at stand-alone multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities. A minority of respondents worked in other treatment settings, with the exception of respondents from New Brunswick, where the volume of responses were more balanced across rural and urban settings. Many respondents from New Brunswick also worked in secondary and tertiary care, or community and long-term care facilities. Notably, with the exception of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, few or no respondents worked in publicly funded stand-alone facilities or hospitals.

Availability, Access, and Funding for Non-Pharmacological Treatments

What follows are summaries of the reported availability, access, and funding for non-pharmacological treatments across the country based on limited responses from the Environmental Scan survey and from consultations. For the purposes of the survey and this report, the term “availability” is meant to represent the concept that treatment modalities are currently being offered by health care providers and facilities in Canadian jurisdictions. In contrast, “access” is meant to indicate the ability to receive the treatment (i.e., ease of access) and level of integration into the chronic pain treatment pathway.

Findings are not a representative quantification of the actual availability or level of access to treatments, or of the exact funding structures in place, but rather a snapshot of the perceived present context in Canada from the perspective of the respondents. There are caveats that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Respondents were invited to indicate which treatment modalities were available in different treatment settings in their jurisdictions. It is important to emphasize that findings represent the proportion of the total number of respondents to any question in each jurisdiction. Hence, the reported level of availability may have been influenced by the total number and type of respondents from each jurisdiction. In addition, many respondents many not have had knowledge of certain treatments because of the area of expertise, treatment setting, or geographical location, and may not have provided an answer for each modality. Hence, the reader should not infer that, for example, if 25% of respondents reported a treatment modality as not available to mean that 75% of respondents reported it as available. In general, there was a higher proportion of non-response to questions about psychological modalities.

Physical Treatments

Availability

Data from survey feedback on the availability of physical treatments in each province is presented in Appendices 2 to 8. Additional physical treatments identified by respondents that were not listed in the survey questions are presented in Appendix 9. Based on the percentage of respondents indicating that a particular physical treatment modality was not available in their jurisdiction, British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario had the greatest proportion of respondents indicating the availability of physical treatments, while New Brunswick and Saskatchewan had the lowest. Across the provinces, with the exception of Saskatchewan, deep brain stimulation was consistently reported as not available by 25% or higher of respondents. Animal-assisted therapy and music therapy were other treatment modalities reported as not available by greater than 20% of respondents in most of the provinces, with the exception of Alberta and British Columbia. Most physical treatments listed in the survey were available in urban settings in all of the provinces. Quebec, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan had the highest proportion of respondents indicating the availability of physical treatments in rural settings. A higher proportion of respondents in Ontario, Saskatchewan, British Columbia, and New Brunswick indicated that physical treatments were more likely to be available in secondary health care facilities compared with primary care or ambulatory care. Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia had the highest proportion of respondents indicating the availability of physical treatments in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities. British Columbia, Manitoba, and Alberta had the highest proportion of respondents indicating the availability of physical treatments in community care. Across the provinces, few respondents indicated availability for most of the physical treatments in remote, research institute, long-term care, and home care settings. Based on geography, the availability of physical treatment modalities was lower in rural settings than urban settings, and lowest in remote settings.

Access

Data regarding ease of access (i.e., whether treatments are widely available, no referral needed or easy to obtain a referral, funded or affordable for most patients) to non-pharmacological physical treatments across the surveyed jurisdictions is presented in Appendix 10. Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario had the highest proportion of respondents indicating that physical treatment modalities were very easy to access. Saskatchewan and New Brunswick had the highest proportion of respondents indicating that physical treatment modalities were not at all easy to access. Deep brain stimulation, prolotherapy, implantable nerve stimulator, spinal cord stimulation, animal-assisted therapy, music therapy, and aromatherapy had the highest proportion of respondents across the provinces indicating these treatment modalities were not at all accessible. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, or TENS, chiropractic care, spinal manipulation, massage therapy, physical therapy, hot-cold treatments, positioning, endurance exercise, strength training, and yoga had the highest number of respondents indicating that these physical treatment modalities were very accessible. Of note, although these physical treatment modalities were reported as very accessible by survey respondents, they are often not publicly funded.

Funding

Data illustrating funding models in use for non-pharmacological physical treatments across the surveyed jurisdictions is presented in Appendix 11. Across the provinces, private insurance and patient out-of-pocket payments represented the funding models with the highest proportion of respondents. However, several respondents noted that, while coverage with private insurance varies according to terms of individual plans, it is often insufficient to accommodate long-term chronic pain treatment services from some health care professionals such as chiropractors, or to provide any coverage for services from other health care professionals such as occupational therapists. In general, physical treatments are funded publicly when the service occurs under the umbrella of hospital in-patient care or select outpatient or ambulatory clinics. However, there are extensive waiting lists for publicly funded services. Workers’ compensation or automobile insurance were also listed by respondents as additional opportunities for patients to gain access to funding for physical treatments outside of publicly funded services. New Brunswick and Quebec had the highest proportion of respondents who indicated that public funding is available for some treatments (such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy), although wait lists are long for these services, while Saskatchewan had the lowest proportion of respondents. Alberta and Quebec had the highest proportion of respondents who indicated that public funding is available if certain criteria are met.

Information was shared on several jurisdiction-specific funding initiatives. Survey respondents from Manitoba indicated that partial coverage for chiropractic services is provided with a patient copayment for a maximum of seven visits per calendar year. Respondents from British Columbia shared that the British Columbia Medical Services Plan subsidizes 10 total visits to allied health professionals for low-income residents qualifying for health care premium assistance. However, respondents noted certain limitations of this program, particularly for patients on long-term disability who either require a greater frequency of visits per year or utilize more than one type of practitioner. In addition, patients may have to pay out of pocket to cover the portion of practitioner’s fees not funded through the province, preventing some from accessing their services through the program (Dr. Jay Robinson, President, British Columbia Chiropractic Association, Richmond, BC: personal communication, 2018 Jul 31). This concept of partial and insufficient public funding limiting access was reinforced by multiple survey respondents and stakeholders. There are other provincially funded programs available such as the Arthritis Rehabilitation and Education Program (AREP).23 The program is funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care through Local Health Integration Networks. A team of occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and social workers provide a range of services including rehabilitation services, guidance on self-management strategies in the home, workplace and community, and individual and group education sessions for patients with arthritis.

Across the provinces, few or no respondents indicated that foundational, grant, or in-kind funding is used to fund non-pharmacological physical treatments. Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D) Canada is an example of a grant-funded program.24 It is a community-based education and exercise program for people with hip and knee osteoarthritis supported by a grant from the Ontario Trillium Foundation. The program provides evidence-based training courses for health professionals involved in the management of osteoarthritis so that they can provide education and exercise sessions to patients. The British Columbia Chiropractic Association noted the existence of several member-funded initiatives where chiropractic services are being provided to relieve physicians from providing musculoskeletal care in order to establish evidence to support future public funding requests.25,26

Psychological Treatments

Availability

Data from each province is presented in Appendices 12 to 18. Additional psychological treatments identified by respondents that were not listed in the survey questions are presented in Appendix 19. Based on the percentage of respondents indicating a particular psychological treatment modality was not available in their jurisdiction, Saskatchewan and Manitoba had the greatest proportion of respondents indicating that psychological treatments were available while New Brunswick and Ontario had the lowest. Across the provinces, with the exception of Saskatchewan and British Columbia, virtual augmented reality was consistently reported as not available by 25% or higher of respondents. Hypnosis was also reported as not available by respondents in British Columbia, New Brunswick, and Ontario. Most psychological treatments listed in the survey were available in urban settings in all the provinces. Quebec and Manitoba had the highest proportion of respondents who indicated the availability of psychological treatments in rural settings. A higher proportion of respondents in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia indicated that psychological treatments were more likely to be available in secondary health care facilities compared with primary care or ambulatory care. Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia had the highest proportion of respondents who indicated the availability of psychological treatments in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities. Manitoba and New Brunswick had the highest proportion of respondents who indicated the availability of psychological treatments in community care. Across the provinces, few respondents indicated the availability for most of the psychological treatment modalities in remote, research institute, long-term care, and home care settings. Based on geography, the availability of physical treatment modalities was lower in rural settings than urban settings, and lowest in remote settings.

Access

Data regarding ease of access (i.e., whether treatments are widely available, no referral needed or easy to obtain a referral, funded or affordable for most patients) to non-pharmacological psychological treatments across the surveyed jurisdictions is presented in Appendix 20. Manitoba, British Columbia, and Alberta had the highest proportion of respondents who indicated that psychological treatment modalities were very or somewhat easy to access. Saskatchewan and Quebec had the highest proportion of respondents indicating that psychological treatment modalities were not at all easy to access. Across the provinces, virtual and augmented reality and hypnosis had the highest proportion of respondents indicating that these treatment modalities were not at all accessible. Most of the psychological treatment modalities were categorized as somewhat easy to access. A few of the respondents commented that treatments that require little training to deliver (including mindfulness, meditation, relaxation, and breathing) are more accessible through the community, Internet, and phone apps, whereas other modalities including in-person cognitive behavioural therapy and psychotherapy that require more specialized training are less accessible and have longer wait lists.

Funding

Data illustrating funding models in use for non-pharmacological psychological treatments across the surveyed jurisdictions is presented in Appendix 21. Similar to non-pharmacological physical treatments, private insurance (often only covering a portion of psychological services) and patient out-of-pocket payments represented the funding models reported as in use by the highest proportion of respondents across the provinces. One respondent noted that workers’ compensation or automobile insurance may cover psychological treatments in rare cases. Manitoba and New Brunswick had the highest proportion of respondents who indicated that public funding is available for some services (such as mindfulness), while Alberta and British Columbia had the lowest proportion of respondents indicating that public funding is available for most services. Respondents from Quebec and Saskatchewan indicated that public funding is used if certain criteria are met. Across the provinces, few or no respondents indicated that foundational, grant, or in-kind funding is used to fund non-pharmacological psychological treatments.

Factors Affecting Access to Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Respondents were asked whether there were specific criteria that a patient must meet first to obtain a referral, and subsequently to gain access to non-pharmacological treatment. The highest proportion of respondents indicated that patients did not need to meet specific criteria to obtain a referral for non-pharmacological treatment (29% yes, 41% no, 31% no answer). This finding may have been influenced by the fact that a large proportion of the respondents were community-based allied health professionals. Feedback from survey respondents highlighted that many of the treatments do not require a referral unless an individual is trying to access publicly funded services or seeking reimbursement for treatment through private insurance. Further, during consultations, it was raised that the requirement for a referral may not be the actual impediment to access; rather, that wait times following referral may create a barrier to receiving care (Dr. Greg Siren, myo Clinic, Victoria, BC: personal communication, 2018 Jul 27). Another related issue raised during the consultations is the burden of paperwork and red tape that can significantly lengthen or impede the referral process for publicly funded pain treatment services (Chantal Arsenault, Primary Care Nurse Practitioner, Moncton Primary Healthcare Clinic, Moncton, NB: personal communication, 2018 Aug 10).

Based on the total number of responses received, the highest proportion of respondents indicated that there were criteria for gaining access to (i.e., receiving) non-pharmacological treatments (41% yes, 34% no, 25% no answer). However, most of the feedback highlighted the importance of the ability to pay for non-pharmacological treatments as opposed to specific clinical criteria for access. Several respondents indicated that physician referral is required to access certain publicly funded services including multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities and physiotherapy. One respondent in Ontario identified specific criteria (age less than 18 or more than 65 years, or on disability insurance) required to gain access to public physiotherapy services.

Policies, Frameworks, or Guidelines Used to Guide Patient Selection for Non-Pharmacological Treatment

The majority of respondents stated that they were not aware of or were not using any specific Canadian policies, frameworks, or guidelines to guide the selection of patients for non-pharmacological treatments beyond the diagnosis of chronic pain. Some respondents indicated awareness of national evidence-based guidelines developed by Health Quality Ontario, the Canadian Chiropractic Association, and the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative. Across the provinces, most respondents indicated the need for further guidance (i.e., guidelines, frameworks, policies, clinical pathways) to provide direction for providing non-pharmacological treatments for chronic non-cancer pain.

Several Canadian evidence-based guidelines for the use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic non-cancer pain were identified by the literature search (Table 3). Common themes in recommendations for general non-cancer pain management include the following:

- Management of chronic pain should be delivered through a multidisciplinary approach and include non-pharmacological treatments.

- Non-pharmacology should be considered as a component of first-line treatment in combination with non-opioid pharmacotherapy.

- Optimization of non-pharmacological therapy and non-opioid pharmacotherapy should be achieved before initiating opioids.

Table 3: Canadian Guidelines for the Use of Non-Pharmacological Treatments in Chronic Non-Cancer Pain

| Guideline Development Group or Centre (Release Date) | Key Recommendations Related to Non-Pharmacological Treatmentsa |

|---|---|

| Chronic Non-Cancer Pain | |

| Health Quality Ontario (2018)27 |

|

| National Pain Centre at McMaster University (2017)12 |

|

| SickKids Hospital (2017)28 |

|

| Knee Osteoarthritis | |

| The Ottawa Panel (2017)29-31 |

The following interventions are recommended approaches to reduce pain, improve physical function, and quality of life for patients with knee osteoarthritis:

|

| Hip Osteoarthritis | |

| The Ottawa Panel (2016)32 |

|

| Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis | |

| The Ottawa Panel (2017/2016)33,34 |

|

| Chronic Low Back Pain | |

| Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative (2018)35 |

|

| Toward Optimized Practice/Institute of Health Economics (2017)36 |

For patients with chronic low back pain (more than 12 weeks since pain onset), the following are recommended:

|

| Fibromyalgia | |

| Canadian Pain Society (2013)37 |

|

| Neuropathic Pain After Spinal Cord Injury | |

| Canadian Pain Society (2016)38 |

The following are recommended as third-line therapy for the management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury:

The following is recommended as fourth-line therapy for the management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury:

|

| Neck Pain- and Whiplash-Associated Disorders | |

| Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative (2016)39 |

|

a Please see guideline for full list of recommendations.

EMG= electromyography; FM = fibromyalgia; JIA= juvenile idiopathic arthritis; NAD = neck pain and its associated disorders; SMT = spinal manipulation therapy; WAD = whiplash-associated disorders.

Barriers and Facilitators Affecting Access and Availability to Non-Pharmacological Treatments

The following section describes the factors (barriers and facilitators) affecting the availability of and access to non-pharmacological treatments across jurisdictions. When inquiring about barriers and facilitators, we chose the approach of asking about how often factors acted as barriers or facilitators rather than whether they were relevant barriers or facilitators. Of note, not all respondents provided an answer for each barrier and facilitator.

Barriers

Barriers to the availability of and access to non-pharmacological treatments reported by survey respondents are presented from a pan-Canadian perspective in Appendix 22.

Funding, Referral, and Reimbursement

The barrier identified by the greatest proportion (59%) of survey respondents (as always or very often a barrier) was lack of public funding. Based on consultations, from the British Columbia primary care perspective, funding is almost always an issue in front-line care, particularly for the hiring of allied health professionals (e.g., physiotherapists) as part of primary health care teams (Barb Eddy, Adjunct Professor, UBC School of Nursing; Family Nurse Practitioner, Primary Care, Downtown Community Health Centre, Vancouver Coastal Health, Vancouver, BC: personal communication, 2018 Aug 3). Another challenge raised during consultations was the lack of extended health coverage available for chronic pain patients who are unable to work, or for patients who work on a short-term contract basis without extended benefits. Without coverage through private insurance, public funding accessible through disability coverage may be insufficient (Dr. Jay Robinson: personal communication, 2018 Jul). One stakeholder noted the presence of an income gradient, specifically in patients with chronic back pain, observing that greater household income is associated with an increased likelihood of seeking care that is not publicly funded (e.g., physiotherapy, chiropractic care), while the inverse is true for seeking care from a family physician.40,41

More than 40% of survey respondents indicated that a lack of reimbursement for aspects of care, and patient and provider perception that payment for treatments are going to be out of pocket were always or very often a barrier to care. Lack of referrals by primary care physicians to allied health professionals was highlighted as a major barrier to accessing non-pharmacological treatments. Some of the reasons stated by survey respondents were lack of awareness, misconceptions about treatment practices and safety of the treatments, and not wanting to financially burden patients who may not have access to extended health benefits. This was corroborated during consultations, with one stakeholder noting that if the primary care physician is aware that the patient cannot access public funding for services they are being referred to, they may rely on treatments for which public funding is accessible. In contrast, during consultations, it was noted that physicians might not consider the potential cost of non-pharmacological interventions when referring patients to receive care that requires public coverage (Dr. Greg Siren: personal communication, 2018 Jul). Views were also shared about continuity of care. One stakeholder highlighted the challenges associated with allocating short-term grant funding toward the expansion of chronic pain services. The feasibility and sustainability of introducing new offerings supported by finite funding may be limited given the potential for disruption and discontinuation of services (Barb Eddy: personal communication, 2018 Aug).

In addition, potential disparities in the availability and funding of certain disciplines within multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities were noted. For instance, private chiropractic care is offered within private facilities (e.g., CHANGEpain, British Columbia42), but is not offered through publicly funded facilities. There may also be a lack of understanding among primary care physicians about the potential value of non-pharmacological treatment, although efforts to educate practitioners are underway (Dr. Greg Siren: personal communication, 2018 Jul).

Geography, Logistics, and Access Barriers

Survey respondents in Ontario and consultation participants also highlighted that lack of public transportation to clinics and services is an issue for many patients. Availability and accessibility of non-pharmacological treatments and specialized practitioners tend to decline with distance from urban centres.43-45

The issues of geography and transportation were further addressed during stakeholder consultations. Notably, in British Columbia, it is a significant challenge for residents of rural and remote areas (e.g., Powell River, Northern British Columbia) to access care, as hours of travel (sometimes by boat or plane) may be required to access certain non-pharmacological treatments (Dr. Greg Siren: personal communication, 2018 Jul). This may be the case in other jurisdictions serving rural and remote populations. As well, if patients have access to services in urban centres, they may lose that access if they relocate and the same services are not available. One stakeholder shared the experience of treating patients in an urban centre who subsequently returned to rural or remote locations to find a paucity of services. This motivated some patients to come back to urban centres to reobtain access (Dr. Brenna Bath, Associate Professor, School of Rehabilitation Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK: personal communication, 2018 Aug 22). Another stakeholder shared experiences from Saskatchewan, where the Non-Insured Health Benefits program may provide funding for non-pharmacological treatments to Indigenous populations living in northern communities. However, the patient may be required to seek care at the closest available provider, which may not be the most appropriate in all circumstances (Dr. Brenna Bath: personal communication, 2018 Aug). Further, group travel may be required, which can extend the duration of travel; travel conditions are often suboptimal (e.g., weather, prolonged sitting, rough roads), which may be challenging for patients with pain (Dr. Brenna Bath: personal communication, 2018 Aug).

Logistical barriers to accessing services may also occur locally. Local transportation such as HandyDART services, which chronic pain patients with mobility challenges may require to help them attend appointments, may not be available in all municipalities (Barb Eddy: personal communication, 2018 Aug). HandyDART is a shared ride service provided for passengers with physical or cognitive disabilities who are unable to use conventional public transportation.46 Logistical challenges may also arise for individuals who are low-income, homeless, or experiencing substance use or mental health disorders. One area where there is a high proportion of residents with these experiences is the downtown eastside of Vancouver, British Columbia.47,48 One stakeholder shared perspectives on patient-related barriers from working in primary care in the downtown east side of Vancouver, British Columbia and described potential challenges in accessing services as a result of a patient’s ability to attend appointments. For instance, even if referrals are made and appointments are set up on behalf of the patient, lack of access to a telephone (or other means of communication) or transportation may mean they cannot access care without considerable support. It was noted that patients with mental health and substance misuse conditions might have unique challenges (Barb Eddy: personal communication, 2018 Aug). Beyond this, patients may be living with conditions that make it difficult to receive treatment for their physical health — for example, trauma-related injuries that involve aversion to physical touch because of the risk for re-traumatization, which may require closer collaboration between mental health care providers and other members of the patient’s care team (Barb Eddy: personal communication, 2018 Aug)

Wait Times

Many survey respondents did not respond to the question asking if wait times for access to non-pharmacological treatments are an issue in their jurisdiction. Based on the limited feedback received, wait times were a major or moderate issue in the majority of responses that were received from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan.

Service Availability

Greater than 40% of survey respondents identified a lack of coordination by multiple providers (including integration of non-pharmacological with pharmacological treatment approaches), and a lack of access to pain specialty care (i.e., pain specialist practitioners or clinics) as barriers occurring always or very often.

Several observations were shared about access to specialty care. One barrier to access noted by a consultation participant was the closure of multidisciplinary chronic pain clinics, or multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities (Dr. Brenna Bath: 2018 Aug). One stakeholder noted that even in team-based primary care settings that incorporate non-physician expertise and services including mental health services, certain non-pharmacological modalities may be unavailable and patients may need to be referred into the community for services such as physiotherapy, chiropractic care, and acupuncture, which depends on their individual ability to pay. Or services offered may be limited due to practitioner capacity (Barb Eddy: personal communication, 2018 Aug). In other circumstances, some practitioners providing non-pharmacological treatments working in outpatient clinics (e.g., physiotherapists working in community clinics in Saskatchewan) may receive salaries through public funding but only have capacity to serve a limited number of patients (Dr. Brenna Bath: personal communication, 2018 Aug).

Language and Cultural Barriers

Inability to address religious, cultural, or societal barriers to care and patient literacy were the barriers reported to be rarely or never an issue to the availability and access to non-pharmacological treatments. In contrast, language was identified as a barrier to access by a stakeholder who works for an organization that provides pain treatment services to a clientele of mostly newcomers to Canada. They noted that while funding for translation can be available within the public setting, the ability to refer the patients to a private clinic is restricted where translation assistance is required. Typically, translation services are either not offered in the private clinics or, if available, must be paid for out of pocket by the patient (Chantal Arsenault, Primary Care Nurse Practitioner, Moncton Primary Healthcare Clinic, Moncton, NB: personal communication, 2018 Aug 10).

Facilitators

Facilitators of the availability of and access to non-pharmacological treatments reported by survey respondents are summarized from a pan-Canadian perspective in Appendix 23.

Funding, Referral, and Reimbursement

There were inconsistent views shared via survey respondents on whether funding was a facilitator. Greater than 50% of respondents noted that enhanced funding or more straightforward funding was always or very often a facilitator; conversely, 18% indicated that it was rarely or never a facilitator in their jurisdiction. During consultations, one stakeholder noted that establishing and increasing partnerships between the public and private sectors may be helpful to improve access to non-pharmacological pain treatments. One example that was used to illustrate this point relates to the provision of care to patients who are covered for pain services under the local social assistance program. They explained that the ability to effectively care for these patients is often constrained by limited capacity and limited access to different pain treatment options in the publicly funded centres that serve that population. The participant considers that if the social assistance programs could offer such services in partnership with the private sector, these patients could potentially get treated earlier and have better results (Chantal Arsenault: personal communication, 2018 Aug). Capacity was addressed by survey respondents as well, with more than 20% of respondents indicating that an increase in dedicated practitioners’ time was sometimes a facilitator in their jurisdiction.

Contextualizing and Personalizing Care

During consultations, the issue of the location of pain services and facilities was raised by one stakeholder. Some services may be localized to hospitals, which can be a traumatic setting for certain groups of chronic pain patients. Localizing chronic pain treatments to centres where patients can go to get their basic services may improve access for this patient population (Barb Eddy: personal communication, 2018 Aug). One stakeholder commented on the role of thoughtfulness around counselling services, and trauma-based counselling services in particular, as an integral part of the care pathway (Barb Eddy: personal communication, 2018 Aug).

Technology

Technology may bridge rural and remote access gaps, allowing practitioners to provide care at a distance. Literature highlighted by stakeholders explores the use of remote presence robots and video conferencing to support the provision of non-pharmacological care.49-52 Some of these technologies may have the potential to facilitate better access to care.

Education and Interprofessional Collaboration

Another facilitator identified through the survey and consultations was improving education on the management of chronic pain with non-pharmacological modalities for practitioners in rural and remote areas, and also for primary care physicians.49 For example, one model has been implemented in Quebec, where physiotherapists are engaged to help train family medicine residents and engage in interprofessional management approaches, and there is interest in extending this to other jurisdictions.41 More than 50% of survey respondents indicated that connectivity between health care professionals, multidisciplinary care provision, and training in the provision of non-pharmacological care were always or very often facilitators. Somewhat related, more than 50% of survey respondents considered improved awareness or inventory of non-pharmacological options available, and evidence to support the use of non-pharmacological strategies, to be factors that were always or very often facilitators of availability and access.

Strategies to Improve Availability and Access to Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Most survey respondents were not aware of any strategies or solutions currently being considered or implemented aimed at improving the availability of and access to non-pharmacological treatments in their jurisdiction. The following are strategies that were identified through survey feedback and from the literature search.

Pain Strategy Initiatives

Canada does not currently have a national pain strategy.2,53 In partnership with the Canadian Pain Coalition, the Canadian Pain Society announced a strategy at a pain summit in 2012, but it was never adopted by the federal government.53 In addition, the Canadian Pain Coalition, a national framework of patient pain groups, and health professionals and researchers involved in chronic pain, ceased operation due to a lack of funding in 2017.54 Several pain strategy initiatives are underway to help create coordinated long-term solutions to reduce the prescription of opioids and increase the utilization of alternative treatment options, including non-pharmacological therapies, for the management of chronic pain in Canada.

McMaster Health Forum

The McMaster Health Forum convened a stakeholder dialogue in December 2017 on the subject of developing a national pain strategy for Canada.55 With the support of the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Pain Research and Care, the dialogue brought together 24 participants from across Canada. Improving primary care-based chronic pain management and creating and expanding interdisciplinary specialty care teams was identified as one of the approaches for developing a national pain strategy.

The Coalition for Safe and Effective Pain Management

The Coalition for Safe and Effective Pain Management was formed in February 2017 to develop strategies to reduce the prevalence of opioid prescribing in Canada by optimizing an interprofessional, patient-centred, collaborative approach to evidence-based, non-pharmacological pain management.56 The coalition includes members from national associations for medical pain management, nursing, physiotherapy, psychology, chiropractic care, occupational therapy, patient groups, and health system experts.57 In March 2017, the coalition was added as a signatory of the federal government’s Joint Statement of Action to Address the Opioid Crisis.56,58 An interim report highlights a proposed approach to pain management in Canada, which involves improving the integration of and access to non-pharmacological alternatives. Several priorities for implementation were identified including the development of comprehensive strategies across the provinces and territories to optimize alternatives prior to initial opioid prescription and the establishment of pain pathways in primary care settings that optimize non-pharmacological pain management at points of care where opioids are commonly prescribed.

Chronic Pain Network

The Chronic Pain Network was awarded $12.5 million in 2016 from CIHR under Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR).59 The Chronic Pain Network is a national collaboration of patients, researchers, health care professionals, educators, industry, and government policy advisors brought together to direct new patient-oriented research in chronic pain, train researchers and clinicians, and translate findings into knowledge and policy.60 The network provides funding to 20 research projects covering population studies, behavioural studies, basic science, and clinical trials.

Provincial Initiatives

Several provinces including, but not limited to, Alberta,61 British Columbia,62-64 Ontario,65 and Saskatchewan66,67 have embarked on developing pain strategies with the intention to establish a unified approach to ensure timely access to chronic pain management services at the provincial level.

The Ontario provincial government has invested 17 million annually (beginning in 2016) to create or enhance 17 multidisciplinary chronic pain clinics across the province.68 Ontario is also expanding Rapid Access Clinics to help people with hip, knee, and lower back pain obtain treatment faster.69 The program is designed to reduce wait times through a coordinated triage process following referral from family physicians, with the intention of preventing unnecessary medical procedures (including imaging and surgery) and allow patients to access treatment options faster (including referrals to physiotherapy and chiropractic treatment). Rapid Access Clinics build on the framework of the lower pain pilot program ISAEC‒Inter-professional Spine Assessment and Education Clinics that was launched in November 2012. The Centre for Effective Practice has also created TheWell, described as “practical tools and resources for primary care.”70 TheWell provides a tool for chronic non-cancer pain, including an inventory of resources, including non-pharmacological services, available in each Local Health Integration Network across Ontario.70

SpineAccess Alberta is a similar project in Alberta. This pilot program is evaluating a new model of care for back pain by creating multidisciplinary team triage centres to help reduce unnecessary consultations and imaging.71 Other groups, including PainBC and SaskPain, are also working to obtain provincial funding for multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities.53

In British Columbia, the Pain BC Allied Health & Nursing Working Group is developing a primary care referral tool for family physicians to increase their knowledge of the role of each allied health profession in managing chronic pain and to assist them in referring patients for non-pharmacological care of pain.62,72 British Columbia is also increasing efforts to educate physicians on managing chronic pain (including the provision of non-pharmacological interventions) through the GPSC‒General Practice Services Committee Practice Support Program, which provides learning modules on pain management.73 Pain BC also holds educational workshops and webinars on the management of chronic pain for various practitioners such as physicians, chiropractors, and registered massage therapists,74 and offers peer support groups to help forge connections between patients with shared perspectives and assist in the navigation of health care and community resources for chronic pain.75

Quebec has created a pain registry of 10,000 patients for clinical and research purposes as part of a strategic initiative of the Quebec Pain Research Network.76,77 This database will provide clinical and epidemiology research to better understand chronic pain to improve on pain management and treatment.

Initiatives to Increase Access to Pain Specialists and Allied Health Care Professionals

The following represent a few examples of initiatives that are taking place across Canada to connect primary care providers with pain specialists and to increase access to allied health care professionals in community and rural settings.

Champlain BASE eConsult

The Champlain BASE (Building Access to Specialists through eConsultation) eConsult service is a secure online platform that provides primary care providers with quick access to specialist advice for their patients.78 Funding for operational support and research has been received from the Ontario Ministry of Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Bruyère Research Institute, the University of Ottawa Department of Medicine, and the CHEO Academic Health Science Centres Alternate Funding Plan Innovation Fund.79 The Champlain BASE eConsult service allows a primary care provider to submit a non-urgent, patient-specific question to a participating specialty to provide guidance on how to treat the patient, or recommend a face-to-face referral.80 Since its launch in 2010, a total of 33,327 cases have been completed by 1,355 registered primary care providers (1,160 family physicians and 195 nurse practitioners) from 449 clinics.79 The eConsult service has been shown to reduce wait times for specialist advice, as well as the number of referrals from primary care provider to specialist care.81,82 The service is currently accessible in Ottawa and surrounding communities, but there are plans to expand the service across Ontario and discussions are currently being held with eHealth services in the provinces of Manitoba and Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as several national agencies representing Canada’s northern communities.83

Project ECHO

Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) was launched in April 2014 as a telemedicine-based mentoring strategy to connect primary care practitioners from across Ontario in remote, rural, or underserved communities with inter-professional pain specialist teams (consisting of psychiatry, pain medicine, neurology, addiction medication, family medicine, psychology, nursing, social work, physical therapy, occupational therapy, pharmacy, and chiropractic services) via weekly video-conferencing sessions.84,85 Project ECHO is funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health.85,86 Unlike Champlain BASE eConsult, there is no patient relationship made between the ECHO hub members and the cases presented in the ECHO sessions.85 All primary care providers (including physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and other allied health professionals) gain knowledge from listening to case discussions, creating a growing network of pain management providers. ECHO has linked more than 150 care providers and more than 50 primary care sites since launching the initiative.

Medical Mentoring for Addictions and Pain Network

The Ontario College of Family Physicians and the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario have partnered to develop the Medical Mentoring for Addictions and Pain Network (MMAP).87 MMAP connects family physicians to physicians with expertise in chronic pain and addictions who provide advice and support in the areas of diagnosis, psychotherapy, and pharmacology. Family physicians receive timely advice from mentors on an informal basis through email, telephone, an online discussion forum, and in-person meetings. Formal continuing professional development events such as small group meetings and regional and annual conferences take place regularly to augment the case-specific mentoring discussions.

Atlantic Mentorship Network‒Pain & Addiction

The Atlantic Mentorship Network‒Pain & Addiction (AMN-P&A) is the largest network of pain and addiction providers in Canada.88 Funding is provided primarily from the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness and the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Health and Community Services. It is designed to connect practitioners (including physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychologists, and social workers) with more than 200 pain and addiction providers across Canada. Members meet in small groups three times a year to discuss cases and receive various educational components. Members can also discuss cases with other members in the group via email or online forums.

Integration of Chiropractic Services into Publicly Funded Community Facilities

In 2011, Manitoba initiated a pilot program providing access to chiropractic care within the Mount Carmel Clinic — a provincially funded inner-city community health centre.89 The project was designed to help manage pain in low-income patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain by integrating publicly funded, community-based providers with chiropractors. Results from a study of the project showed a significant reduction in pain in patients suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain with most cases not requiring a referral to another health care provider. A similar project has integrated chiropractic services within a publicly funded, multidisciplinary, primary care community health centre in Cambridge, Ontario.90 A study evaluating the service showed that the majority of patients referred to the service by their physician or nurse practitioner reported a significant reduction in pain. More than three-quarters did not visit their primary care provider while under chiropractic care.

Use of Telehealth Technologies to Increase Access to Physical Therapy

A pilot project is investigating the use of a telehealth team care model to help assess chronic back pain in rural and remote Saskatchewan.49 Real-time video conferencing is used to connect nurse practitioners in rural and remote communities with an urban-based physical therapist who provides guidance for hands-on assessments. The findings from this project will help inform the development of community-based implementation strategies to improve access to physical therapy services in primary health care settings in rural and remote underserved areas.

Although video conferencing may be able to address some unique health care needs when delivering physical therapy services in remote communities, secure video conferencing units are not available in every community.91 A second pilot project is investigating the use of remote presence robotic (RPR) technology for improving access to physical therapy for people with chronic back disorders in northern Saskatchewan communities.91 RPR runs on a wireless connection, eliminating the need for a wired connection normally required for traditional telehealth systems. RPR systems also allow a physical therapist to easily move around a patient, zoom in, and enable screen sharing to facilitate patient education. A recent case report shows that the delivery of interprofessional spinal triage management using RPR in a remote setting is feasible.91 Neither of these technologies are currently widely implemented or funded external to the research setting in Saskatchewan.

Limitations

The findings of this Environmental Scan present an overview of the current context of non-pharmacological treatment of chronic non-cancer pain in Canada based on the perspectives of a limited number of people working in the field. A systematic literature search was not conducted and the report is not intended as a comprehensive review of the topic. The main focus was to evaluate the availability of and access to non-pharmacological therapies delivered by health care and other professionals. Hence, many patient self-led interventions or educational opportunities offered outside of traditional health care contexts were not captured from the target pool of respondents and were considered beyond the scope of this report. The highest proportion of responses were received from chiropractors and physiotherapists. Although these health professionals play an important role in providing non-pharmacological therapies in primary care settings, the views presented may not be representative of other allied health care professionals providing front-line, non-pharmacological treatments (including occupational therapists and psychologists) or other professionals providing complementary or traditional pain therapies (including massage therapists, yoga instructors, and acupuncturists). Furthermore, the overall findings may not accurately represent the perspective of other health care professionals involved in the management of chronic pain (including family physicians, specialist physicians, and nurse practitioners), particularly regarding the availability and access to certain non-pharmacological treatments only provided in publicly funded tertiary care centres including deep brain stimulation, nerve block, implantable nerve stimulators, and spinal cord stimulation. Patients were not included in the development of this report; thus, the results may not reflect patient’s experiences and perspectives as they relate to access to and availability of non-pharmacological treatments. The findings do not address nuances regarding the equity of access for populations facing health disparities such as Indigenous populations. Many respondents noted they were unfamiliar with treatments outside their area of expertise, particularly the psychological treatment modalities (mainly because of the absence or limited response from psychiatrists, psychologists, counsellors, and other mental health professionals), which may have skewed survey results. As noted in the description of project scope, this report does not assess evidence for the clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of included non-pharmacological treatments. The data presented is to comment on availability and accessibility, and not on appropriate use.

The majority of respondents worked in urban primary care settings, at stand-alone private facilities, or at stand-alone multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities. Hence, the generalizability of the findings to other treatment settings and facility types including rural and remote health care settings may be limited. In addition, the survey did not ask explicitly about remote monitoring and treatment, telehealth, or Internet-enabled interventions. We were therefore not able to comment directly on the availability of these modes of care delivery. There may have been an over-representation of the extent to which non-pharmacological treatments are funded out of pocket or through private insurance based on the fact that few respondents worked in publicly funded stand-alone facilities or hospitals. As well, survey feedback may not accurately reflect the extent to which wait times are a barrier for access to non-pharmacological treatments in publicly funded facilities across the jurisdictions. Findings also do not represent the current landscape of the access to and availability to non-pharmacological treatments in areas of Canada where limited or no survey feedback was received including Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and the three territories. Due to the structure of the survey, some of the listed treatment modalities may have been over-represented because of an overlap in treatment provider (such as chiropractic care) and treatment modalities offered by that provider (such as spinal manipulation). Because of the presentation of survey questions related to ease of access, we are not able to discern what aspect (e.g., availability of treatments, whether a referral is required, and affordability) was the main driver for the response. We therefore cannot comment on the specific drivers of accessibility, although this topic is addressed to a certain extent in our discussion of barriers and facilitators. No formal definition of the term “available” was provided in the survey questionnaire. As a result, respondents may have had different interpretations of what was being asked by questions that probed the availability of modalities. Lastly, when inquiring about barriers and facilitators to the availability of and access to non-pharmacological treatment options, we chose the approach of asking about how often factors acted as barriers or facilitators rather than if they were relevant barriers or facilitators. Individuals who did not perceive individual factors as relevant to their context may not have responded.

Conclusion

In summary, most of the non-pharmacological treatments included in the survey were reported to be available in the jurisdictions, particularly in urban settings. Quebec and Manitoba had the highest proportion of respondents indicating the availability of non-pharmacological treatments in rural settings. Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia had the highest proportion of respondents indicating the availability of non-pharmacological treatments in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities. Across the provinces, few respondents indicated availability for most of the non-pharmacological treatments in remote, research institute, long-term care, and home care settings. Based on geography, the availability of non-pharmacological treatment modalities was lower in rural settings than in urban settings, and lowest in remote settings.

Despite survey feedback indicating that most of the non-pharmacological treatments are available in the jurisdictions, respondents reported that access to these treatments is limited due to long wait times for publicly funded services (including those provided by multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities) and the lack of public funding for community-based services such as chiropractic care, physiotherapy, and occupational therapy. Access to these private services in the community may be beyond the reach of many people because of financial constraints unless they are able to pay out of pocket and/or receive reimbursement from third-party funding including private insurance, workers’ compensation, or automobile insurance. Furthermore, although these non-pharmacological treatments have been shown to be most effective when offered as part of a team approach,55 survey feedback indicates that chronic pain management in community settings is seldom provided using a coordinated approach with input from multidisciplinary pain care providers. Many respondents highlighted the lack of referral from primary care physicians as a significant barrier to accessing non-pharmacological treatments.

The barriers to accessing non-pharmacological treatments identified in this Environmental Scan are also present in other countries. For example, many non-pharmacological therapies are not reimbursed by Medicaid, Medicare, or third-party payers in the US.85,92 Integrated health systems such as Kaiser Permanente and the Veterans Health Administration have sought to make multimodal pain care more widely available, even establishing virtual treatment networks relying on telehealth to deliver some non-pharmacological pain treatment modalities to remote areas.85 Despite such efforts, lack of universal health coverage means that many people who cannot afford private insurance do not have access to non-pharmacological treatments.